Chapter Three

Merchant Marine Years – Convoys, Harbors & Union Work

From the bright lights of Carlton Park to the darker horizon of wartime seas, Eli’s years in the U.S. Merchant Marine carried him from Baltimore’s rowhouse streets onto convoy decks where every watch could turn dangerous. This chapter follows those voyages and the union work that later rooted him back on the Baltimore waterfront.

From Ring Lights to Harbor Signals

By the early 1940s, the lights above the boxing ring no longer felt like the brightest thing in Eli’s world. News of the war in Europe and the bombing of Pearl Harbor reached Baltimore rowhouses through crackling radios and headlines stacked in corner shops. The conversations in barbershops, cafés, and corner taverns turned from local fighters and ball games to convoys, enlistment, and ships that never came home.

Eli knew how to keep his balance under pressure. Years in the ring had taught him to live with fear and still move forward. When the Merchant Marine and wartime shipping companies began recruiting in port cities, it offered something that felt familiar: danger, discipline, and a chance to prove yourself for more than just a purse.

Signing On for Convoy Duty

Merchant Mariners were civilians, but in wartime their work moved alongside the Navy and the Coast Guard. Eli’s path into that world ran through Baltimore hiring halls and training piers, where men lined up with sea bags and paperwork, hoping for a berth. Physical toughness helped, but so did an ability to listen, follow orders, and keep your head when the weather or the news turned bad.

He learned new routines: lifeboat drills instead of roadwork, damage-control lectures instead of gym talks, the language of hatches, holds, and cargo manifests. The sea had its own footwork—moving across a steel deck in heavy boots while the ship rolled and pitched under you. One misstep could send a man into the dark.

Long Watches on Blacked-Out Decks

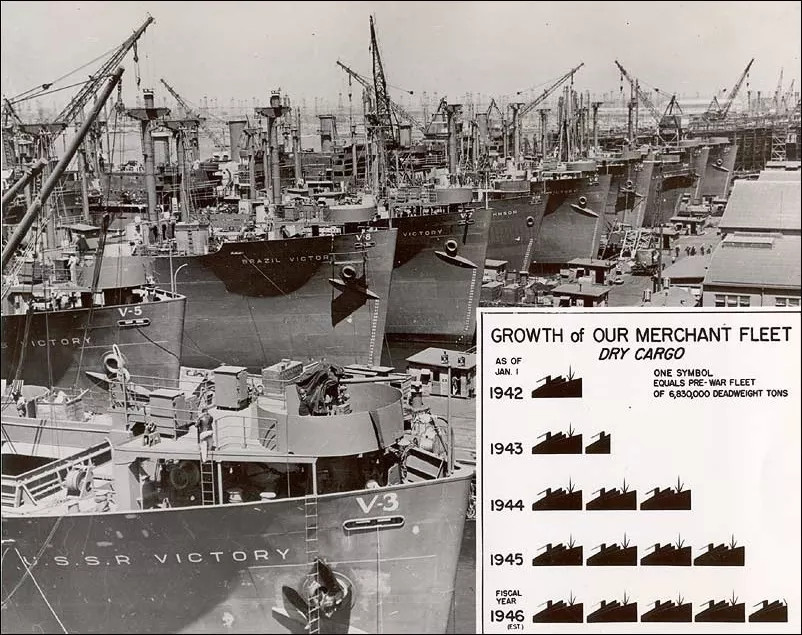

Convoy life was a kind of moving city: tankers, freighters, and escort ships spread out across miles of ocean, all trying to keep formation while the world went dark around them. At night, lights were shaded or covered. Cigarettes were cupped in calloused hands. The only steady glow might come from the signal lamps or the pale wash of the moon on the swells.

Eli’s shifts meant standing watch on blacked-out decks, eyes adjusting to the faint outline of other ships slipping in and out of sight. Somewhere beneath that same water, U-boats hunted along known shipping lanes. A burst of distant gunfire or a flash on the horizon could mean another ship had been hit. In the ring, a punch came from one direction. At sea, danger could come from anywhere.

The work between crises was steady and exhausting—securing cargo, chipping rust, handling lines, helping in the galley when extra hands were needed. It was physical labor that left little room for vanity, but plenty of room for camaraderie. Men from different cities and backgrounds shared coffee, cards, and stories of the neighborhoods they hoped to see again.

Harbors at the Edge of War

Between crossings, there were brief glimpses of the wider world. Convoys ended in ports that carried their own tensions: blackout curtains, air-raid drills, streets crowded with uniforms from half a dozen nations. Harbor bars were filled with a mix of bravado and worry—sailors talking fast on short leave, shipping clerks counting tonnage, local families queuing for rations.

Eli walked those streets with the same habit he’d learned in Baltimore: watching who stood where, who kept order, and who quietly took advantage of the chaos. War magnified everything—courage and fear, kindness and cruelty, heroism and profiteering. It also reminded him that the cargo under his feet on each voyage was more than crates and barrels; it was fuel, food, and equipment that someone far away was waiting on.

Back to Baltimore, Back to the Hall

When the war years eased and convoys grew less perilous, the work did not simply stop. Ships still needed crews. Harbors still needed to move cargo. But men who had risked their lives at sea now asked different questions about pay, safety, and respect. On the Baltimore waterfront, unions became the place where those questions were argued, answered, and sometimes shouted into smoky halls late into the night.

Eli gravitated toward that organizing work. He knew what it meant to stand up to bullies, whether they were alley toughs, corner bookmakers, or company men who treated crews as disposable. He brought to union meetings the same stubborn belief he had carried into the ring—that working men deserved a fair chance, a fair wage, and a measure of dignity no supervisor could take away.

What the Sea Left Behind

The Merchant Marine rarely made front-page headlines, but the work of those ships shaped the outcome of the war and the character of the ports they served. For Eli, the years of convoy duty and union organizing left marks as permanent as any scar—an ease with danger, a distrust of easy promises, and a conviction that solidarity mattered more than swagger.

In Baltimore, the same city where he had once fought under local lights, he now walked the piers and union halls as a man who had seen the world’s horizons and returned with a deeper sense of duty. The sea had not smoothed out his rough edges so much as sharpened his sense of what was worth fighting for.

Chapter Three is the story of those years at sea and on the docks—of convoys that vanished into fog, of ships that limped home, of hiring halls dense with cigarette smoke and shouted names. It is where Eli’s story widens from neighborhood fighter to working seaman and advocate for the men who kept the harbor alive.