Eli’s Early Years in Context

On the left is Eli’s journey from a tight Orthodox home near Patterson Park to years at sea and back again. On the right, the Baltimore streets, docks, and world events unfolding around him.

Eli’s Story

-

Early 1920s – New Roots in East Baltimore

Romanian-born Louis and Russian-born Ella Hanover rent cramped rooms near Patterson Park, keep a kosher home, and raise a growing Orthodox family in a city still learning how to welcome its immigrant neighbors.

View early family photos (placeholder) →

In those early years near Patterson Park, every day was a negotiation: finding work on the docks or in small shops, learning enough English to get by while still thinking and praying in Yiddish, and figuring out which streets felt safe for an openly Orthodox family and which did not. Rent was high, rooms were small, and prejudice was never far away, but the Hanovers stitched together a life out of long hours, Shabbat rest, and a stubborn belief that they belonged here.

-

1921 – Eli is Born

Eli “Ted” Hanover is born into a Yiddish-speaking household where money is short but expectations are high. From the start he shares beds, stories, and space with many siblings in a lively Orthodox home.

Read more about Eli’s early years (placeholder) →

There is no known baby photograph of Eli. Like many working-class immigrant families of the time, the Hanovers simply couldn’t afford to hire a photographer for every milestone. Studio portraits were a luxury, usually reserved for a wedding, a bar mitzvah, or a rare “big occasion,” not for everyday moments in a crowded rowhouse.

The image here stands in as a period illustration, a reminder that Eli’s first years would have looked much like those of countless other Jewish children in East Baltimore—bundled against the cold, passed from arm to arm, growing up in a home where love and worry were both in steady supply, even when money was not. As more family material surfaces, this card will hold whatever stories and memories remain from Eli’s earliest days.

-

1930s – Growing Up Near Patterson Park

Shabbat candles, holiday meals, and Yiddish conversation anchor life inside the rowhouse. Outside, streetcars, stickball, and corner shops teach Eli how to move through a tough but close-knit neighborhood.

Explore neighborhood memories (placeholder) →

For a kid like Eli, Patterson Park was more than a patch of green on a map. It was where older brothers and cousins taught you how to throw a ball, where you learned which benches were “yours,” and where the sounds of Yiddish, English, and a dozen other accents floated together on summer evenings. On Saturdays, after services and a meal at home, the park paths filled with families walking slowly, talking quietly, and keeping an eye on children racing ahead.

The Great Depression meant there was rarely extra money for treats, but there was always something to do: watching men play cards at sidewalk tables, running errands to the corner grocer, or walking down to see the streetcars clatter past. Boys like Eli learned early how to spot trouble, when to keep their heads down, and when to stand their ground if someone mocked their name or their religion.

While these scenes reflect the wider experience of Jewish families around Patterson Park in the 1930s, they also give a likely backdrop to Eli’s own childhood—ordinary days in East Baltimore that quietly shaped the toughness, humor, and loyalty people would later recognize in the man.

-

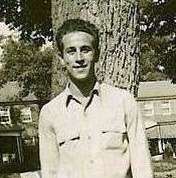

1939–1940 – Stepping into the Ring

As a teenager, Eli finds neighborhood gyms and smoky local fight cards. Fighting as a featherweight, he learns to train hard, take a punch, and keep moving forward under bright lights.

See more from his boxing record (boxrec) →

Surviving records show Eli boxing as a young featherweight on small professional shows at Carlin’s Park in Baltimore between 1939 and 1940. In eight recorded bouts he won seven—three by knockout—building a reputation as a tough, busy fighter who was hard to discourage.

The tickets and clippings that remain hint at the atmosphere: weeknight cards promoted in the local papers, cheap seats filled with dockworkers, merchants, and neighborhood kids, smoke hanging in the rafters as friends shouted his name. For many working-class immigrants, these fights were both entertainment and a chance to prove themselves in front of their own community, and Eli was no exception.

As we continue to gather material, this section will grow to include scans of ticket stubs from Carlin’s Park, newspaper write-ups of each bout, and anysurviving photos of Eli training or stepping through the ropes on fight night.

-

1942–1945 – At Sea with the Merchant Marine

With war spreading across the world, Eli signs on with the U.S. Merchant Marine. Convoys move through dangerous waters; long watches at sea teach discipline, endurance, and quiet courage.

Merchant Marine & union chapter (planned) →

Family stories and union records place Eli among the thousands of merchant seamen who sailed out of Baltimore during World War II, carrying fuel, food, and ammunition across the Atlantic. Like many mariners of his generation, he likely signed onto Liberty ships and freighters that joined long, slow-moving convoys headed toward Europe and the North Atlantic.

Life on board was hard and dangerous. Merchant Marine crews stood watch in blackout conditions, learned to recognize the shape of a submarine wake, and slept in their clothes when the seas were rough or the U-boat threat was high.

Lifeboat drills, gunnery practice, and hours of chipping rust or loading cargo filled the days; at night, men listened to the engines thrum and hoped the escort ships would spot trouble before it reached them.Casualty rates for the Merchant Marine were among the highest of any American service in the war, and official recognition was slow in coming. For Eli, those years at sea seem to have left a mark: a quiet seriousness about work, a habit of reading a room quickly, and a sense that danger could arrive without warning but had to be met head-on. The toughness he once used in the ring now helped him endure storms, long separations from home, and the constant uncertainty of wartime sailing.

As more documents are located—from ship lists, union files, or wartime correspondence—this section will grow to include the names of the vessels he served on, the routes he traveled, and any surviving photos of Eli in his Merchant Marine years.

-

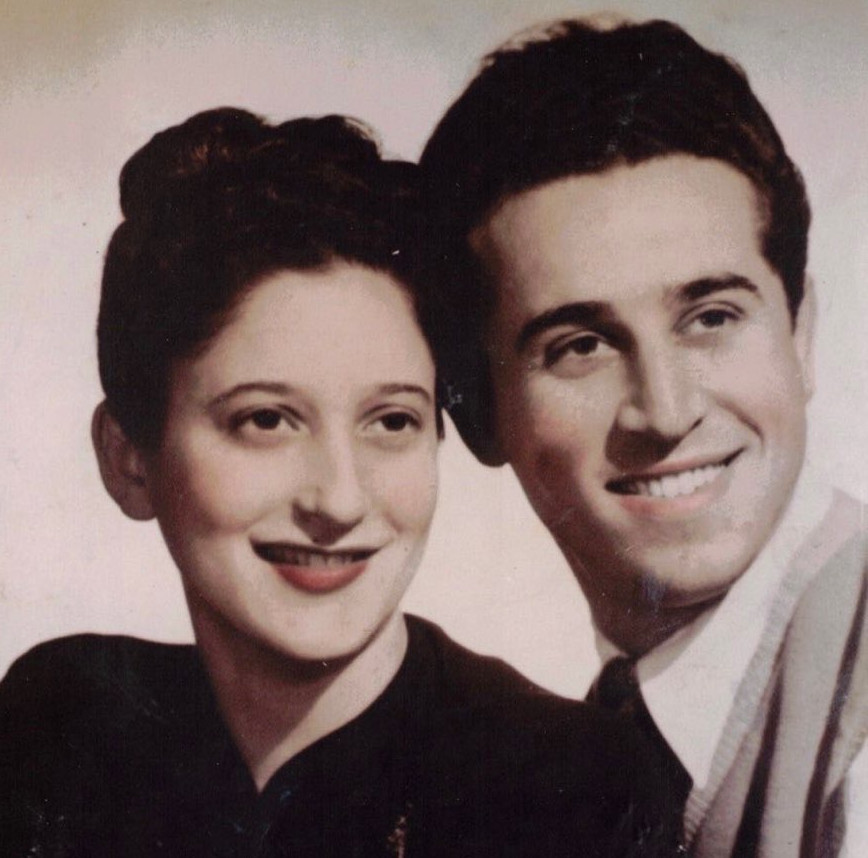

Late 1940s – Coming Home & Meeting Frances

After years at sea, Eli returns to a changing Baltimore. In Frances Michaelson he finds a partner whose humor and strength match his own, and together they are ready to build the family this site celebrates.

Learn more about Eli & Frances (placeholder) →

Like many young couples in postwar Baltimore, they likely met through a web of synagogue friends, neighborhood gatherings, or family introductions. Dates may have been simple: a movie on a weekend night, a walk after shul, or coffee at a crowded kitchen table while parents listened from the next room. What people recall most is the feeling that they “fit” – his toughness and drive balanced by her warmth, practicality, and sharp sense of humor.

Money was still tight, and housing for young Jewish couples could be hard to find, but they married anyway, choosing to build something together rather than wait for perfect circumstances. In photographs from these years, Eli looks proud and slightly protective; Frances looks ready to step into whatever came next. They were part of a generation that moved from the hardship of the Depression and war into a new chapter of rowhouse porches, baby carriages, and family dinners.

As more stories and documents surface, this section will grow to include details of their courtship, wedding day, first apartments, and the arrival of their children – the beginnings of the Hanover family that this site is dedicated to remembering.

Baltimore & the Wider World

-

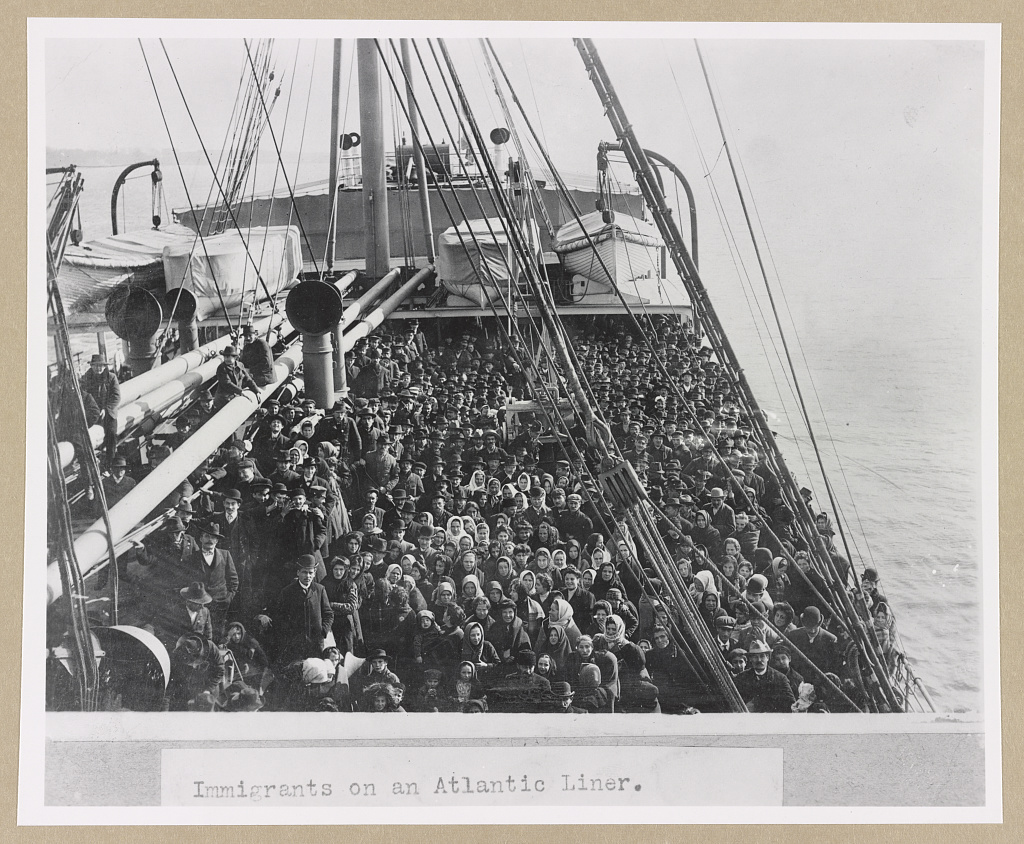

1920s – Immigrant Baltimore

East Baltimore fills with new arrivals from Eastern Europe. Jewish families open groceries, tailor shops, and small synagogues; rowhouses echo with multiple languages and mutual aid societies.

Jewish Baltimore in the 1920s (placeholder) →

In the years when the Hanovers arrive, whole blocks of East Baltimore are turning into patchworks of immigrant life. Pushcarts line the streets, selling bread, herring, and vegetables; shop signs appear in English and Yiddish; and basements or second-floor rooms double as small shuls where men gather to pray before and after long shifts on the docks, in factories, or as peddlers.

Housing is cramped and often shared with other families or relatives just off the boat. Newcomers navigate strict immigration quotas, occasional police harassment, and open antisemitism, even as they search for steady work and a foothold in the city. Mutual aid societies, landsmanshaftn, and synagogue circles help newcomers with doctor bills, funeral costs, and the unpaid rent that can come with a slow week at the market.

Children grow up straddling worlds – attending public school in English, learning prayers and Hebrew after class, and translating for parents at city offices or shops. Streetcars carry workers from rowhouse blocks near Patterson Park down to the harbor and back again, stitching together a daily routine in which faith, hard work, and community are often the only safety net.

As this site grows, this card will link to museum exhibits, oral histories, and scholarly work on Jewish Baltimore in the 1910s–1920s, offering a wider frame for understanding the world Louis and Ella Hanover walked into when they chose this city as home.

-

Early 1920s – Faith & Hard Times

Many immigrant families work as peddlers, longshoremen, and small merchants,

often paid less than native-born workers. Synagogues and holiday rituals provide

stability when wages and housing do not.

Jewish labor & small business (placeholder) →

For families like the Hanovers, every paycheck is stitched together from long days and uncertain work. A father might haul cargo on the docks during the week and push a cart of goods on Sundays; a mother might take in boarders, sewing, or washing to cover rent and food. Pay is low, hours are long, and layoffs or injuries can erase months of effort overnight.

Yet the economic story is not only about struggle. Small groceries, tailor shops, lunch counters, and pushcarts become footholds of independence for Jewish immigrants shut out of better-paying jobs. A narrow storefront on a busy corner can feed a household, support relatives back in Europe, and offer credit to neighbors in even tougher shape.

Religious life and work life overlap. Business owners close early on Fridays to make Shabbat, bring home extra bread before the holidays, and mark the Jewish calendar even when the wider city barely notices. Children absorb both worlds: they help in the shop, run deliveries, or keep an eye on younger siblings, all while learning that every coin matters.

As this site grows, this card will point to studies of Jewish dockworkers, small merchants, and garment workers in Baltimore, helping readers see how families like Louis and Ella Hanover balanced risk, faith, and sheer persistence to keep their households afloat.

-

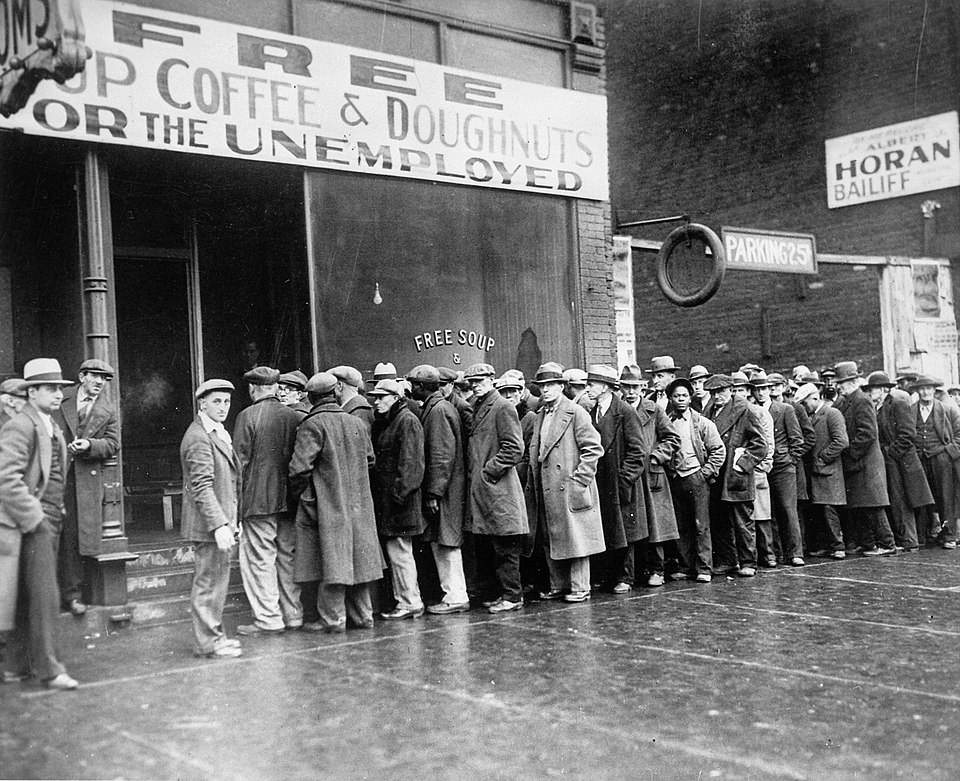

1930s – Depression & Neighborhood Grit

The Great Depression hits working-class districts hard. Families double up in

small houses, older children take odd jobs, and relief lines form, even as

neighborhoods remain tightly knit.

How the Depression shaped East Baltimore (placeholder) →

In East Baltimore, the crash of 1929 is felt not on Wall Street tickers but in empty iceboxes and overdue rent. Longshore work, shop hours, and casual labor all become unpredictable. It isn’t unusual for several branches of a family to share a single rowhouse, taking turns with the beds and stretching every pot of soup one more night.

For Jewish households like the Hanovers, the safety net is a patchwork of synagogue charities, mutual aid societies, and quiet generosity between neighbors. A grocer might extend credit a little longer; a tailor might mend a coat for free; a rabbi might quietly arrange a basket of food before a holiday. Pride and need are constantly in tension, and families do their best not to show how thin things have become.

At the same time, the federal government’s New Deal programs begin to change the feel of the city. WPA crews repair streets and parks; CCC camps send some young men out of town to build roads and plant trees; relief offices open for those willing to endure the paperwork and long lines. Children growing up in this era learn to read the signs: which blocks feel safe, where help can be found, and when to keep their heads down.

For boys like Eli, the Depression years mean early responsibility. A teenager might sell papers, haul coal, or help in a family shop, then head to the park or the gym to burn off the day’s worries. When he later walks into a boxing ring, he carries not just his own weight but the memory of bread lines, crowded kitchens, and a neighborhood that survived by holding tight to one another.

-

1939–1940 – Storm Clouds & Fight Nights

As war breaks out in Europe, Baltimore fight fans crowd into halls and parks for boxing cards where Jewish, Italian, and Black fighters share the bill and small purses become big entertainment.

Boxing in prewar Baltimore (placeholder) →

On the radio, news from Europe grows darker by the week: invasions, air raids, and talk of a war that might spread. On Baltimore’s streets, though, Saturday nights still hum with a different kind of tension — the noise of people lining up for local fight cards, looking for a few hours where the only battles that matter are inside the ropes.

Promoters stack their shows with neighborhood names: tough dockworkers, rail-yard laborers, kids from East Baltimore rowhouses, all willing to trade punches for a payday and a moment under the lights. Jewish, Italian, Irish, and Black fighters share the same posters and the same cramped dressing rooms, even when the rest of the city keeps its distance across invisible color and class lines. In the ring, skill and heart matter more than who your grandparents were or which language they spoke at home.

For working-class fans, a ticket to a boxing show is both escape and education. They read the sports pages for results, learn the names of rising prospects, and argue over who really won last week’s decision. Smoke hangs in the air, bookies whisper in the corners, and kids press close to the railings to watch how courage looks up close.

This is the backdrop for Eli’s own featherweight run: a small but electrified world where local fighters carry the pride of entire blocks into the ring, and where the rhythm of prewar Baltimore can be heard in the bell that starts each round. Before troop ships and convoys, the fight posters and bright bulbs of these nights are the stage on which he first learns to perform under pressure.

-

1942–1945 – Harbor at War

During World War II, Baltimore’s harbor becomes an industrial engine, building and loading ships around the clock. Merchant mariners sail in convoys facing U-boat attacks and harsh conditions.

Merchant Marine service in WWII (placeholder) →

Once the United States enters the war, the familiar harbor around Fell’s Point, Sparrows Point, and Curtis Bay is transformed. Shipyards roar with welding torches, cranes swing over newly laid keels, and whole neighborhoods live by the rhythm of shift whistles instead of church bells. In a city already tied to the water, nearly every family knows someone who now works on a line, a pier, or a ship.

Liberty and Victory ships slide down the ways in rapid succession, built to carry cargo, troops, and fuel across oceans suddenly filled with unseen dangers. Merchant mariners — civilians in uniform-like gear — crew these vessels, sailing in convoys that thread their way through U-boat hunting grounds. They stand long watches on open decks, scan dark horizons for periscopes, and know that a single torpedo can end a voyage in minutes.

On shore, blackout drills dim streetlights and curtained windows along the bay. Workers pour out of night shifts with faces smeared by grease and paint, grab a few hours’ sleep, and return to weld, load, and repair. Women join the yards in growing numbers, learning trades once reserved for men, while unions negotiate wages, safety, and hours in an environment where “round-the-clock” becomes the new normal.

For mariners like Eli, the war years mean long absences from home and a kind of service that is both essential and often overlooked. Cargo ships carry the food, tanks, and ammunition that make Allied victories possible, but the men aboard them rarely receive parades or headlines. Their stories live instead in logbooks, whispered sea tales, and the memories of families waiting on the docks for the next ship to return.

This section will eventually point to records and oral histories that place Eli’s Merchant Marine service inside that larger picture — a Baltimore harbor at war, and a generation of sailors whose courage kept the supply lines alive.

-

Late 1940s – Postwar Shifts

After 1945, returning servicemen seek steady work on the docks, in factories, and in growing unions. Jewish families begin moving outward from the old streets but still return for shul, holidays, and family gatherings.

Baltimore after the war (placeholder) →

In the first years after the war, Baltimore feels both familiar and newly unsettled. Troop trains and transport ships bring men home to rowhouses that have barely changed, yet the world they left behind no longer quite fits. The harbor still hums with industry, but now the talk on the docks and in corner bars is about the G.I. Bill, mortgages, and where the next chapter of life will be written.

Shipyards, steel mills, and waterfront warehouses absorb many returning servicemen, while union halls fill with veterans learning how to bargain for wages, safety, and seniority instead of simply taking whatever work they can find. For Jewish workers, the same neighborhoods that once felt like a first foothold in America now become a crossroads: some families stay close to the old blocks around Patterson Park; others look toward newly built streets in outlying areas, chasing better schools and a little more space.

Synagogues and neighborhood shuls remain anchors, even as congregants begin to scatter. People who move away still come back for High Holidays, weddings, and yahrzeit services, filling pews with a mix of familiar faces and newly suburban accents. On Friday nights and festival days, the old streets briefly feel like they used to, even as the city quietly shifts around them.

At the same time, entertainment districts like The Block, the harborfront, and downtown theaters adjust to a peacetime crowd—sailors on shore leave mingling with returning veterans and newly married couples out for a rare night away from home. It is into this Baltimore, half old-world enclave and half postwar experiment, that Eli returns from the Merchant Marine and begins to imagine a life with Frances, steady work, and a family of their own.

This section will eventually link to maps, photos, and essays tracing how Jewish Baltimore and the city’s working waterfront changed in the years when Eli and Frances were taking their first steps as a young couple.